My Messy Analytics Breakup

Written by

Owen Auch

on

Launching a website — even a simple blog like this one — comes with a lot of decisions. Choosing a front-end framework, hosting provider, domain name, and layout are exhausting, and that’s before sitting down to write anything.

But there was one decision that I didn’t give a second thought — installing Google Analytics. As the de facto analytics standard for sites of all sizes, Google Analytics was a no-brainer to add to Digital Inklings so that I could know how many people are visiting the site and get a little hit of dopamine every time someone reads an article.1 But over the last several months, I’ve thought far more about this mindless decision than all the others. Using Google Analytics has some troubling implications in regard to both privacy and tech monopoly power, so a few weeks ago, I decided to take a principled stand and break up with Google Analytics. I built my own analytics service, which I’m running on Digital Inklings now, and generally felt pretty triumphant. But my breakup with Google Analytics, like all breakups, has been far from clean, and my own moral confusion has served as a valuable lens to think about bigger questions of privacy on the internet.

I’m going to start this article by explaining the problems that Google Analytics presents, then discuss my transition to running my own personal analytics service and the broader questions that it raised. Sometime in the future I’ll write a technical follow-up about how I built the analytics service, which could be of interest to readers that want to try to build something similar on their own sites, or to people who want to see an example of an extremely spartan approach to microservices.

The internet’s all-seeing eye

Google has far from a stellar track record on privacy, but until recently, I’d never considered the troubling implications of using Google Analytics on my website. I’ll explain how it works as simply as possible, and then lay out the problems.

As a developer, installing Google Analytics could not be easier: just create an account with Google and add the small snippet of provided code to each page of your website. The first time you visit a site with Google Analytics while surfing the web, that snippet of code will run and install a cookie. Cookies are a fun name for a little piece of information that a website stores on your internet browser so it can remember something about you. Cookies are generally harmless and valuable — for example, many sites will save a cookie with account information when you first log in so that in the future, they can check the cookie to verify your identity rather than making you log in again.2

Google Analytics also uses its cookie to identify you, but for a different purpose. Once that cookie has been installed, each time you load a page that is running Google Analytics, the same code snippet from before will read your cookie, identify you, and send a message to Google letting them know that you visited that page. Google then cleans up the data and creates beautiful dashboards that the developer (yours truly) can use to get his hit of dopamine.

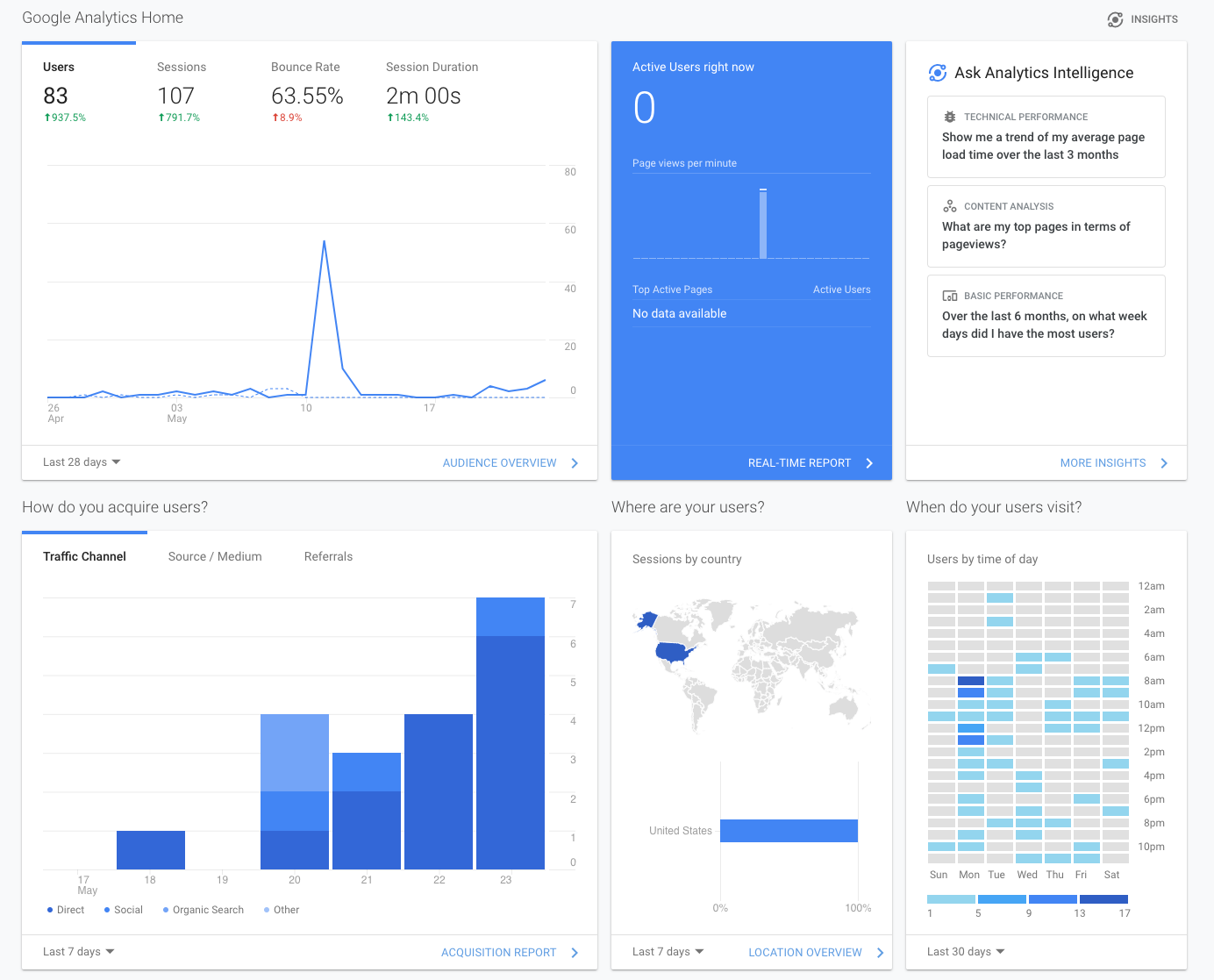

It doesn’t take a data scientist to figure out when I posted an article using this dashboard.

This might not seem like a problem on its face. But the implications become scary when we consider the scale of Google Analytics, both in regard its breadth and depth.

First, the depth of data that Google Analytics captures is remarkable. I mentioned that Google records who you are and what pages you visited, but they also record what device you’re using, how long you stayed on the site, what you clicked on, your geographic location, and what site you came from. Google knows everything that happens on any site running Analytics in click-by-click real time. And because of their cookie, they can track users between different sites running Google Analytics, showing them an even more complete picture of people’s lives on the web.

The depth of the data becomes more concerning when we discuss the breadth of Google’s reach. Google Analytics is used by over 85% of the top 100 thousand sites in the world. Almost every time you load an internet page, Google is reading the cookie in your browser and saving comprehensive data about your visit to that page.

Considering an analogy to the physical world puts this enormous scale in perspective. Imagine that 85% of the locations in your city — public or private, indoor or outdoor, restaurants, homes, doctor’s offices — each had a spy of sorts that stood in the corner with a walkie talkie and a big Google logo on his chest.3 Whenever you entered a place, the Google spy would ask to see your driver’s license, radio into Google HQ that you just arrived, and continuously update Google via radio about all your actions in real time until you left the location.

It’s creepy, but it’s exactly how our online world operates. Google knows where everyone is on the entire internet at all times with very few holes. I’ve written before about the importance of online privacy and the damage caused to society when we lose it, so I don’t feel like I need to make that case again here. But even if having no online personal privacy doesn’t bother you,4 Google’s all-seeing internet eye presents another problem. Google Analytics is free, and as the classic aphorism goes:

If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.

Google Analytics isn’t free out of a sense of charity. Every time a new site adds Google Analytics, Google’s monopoly on internet data strengthens. Google can look at the data on every site that you go to and use it to show you targeted ads or sell you products with a ruthless precision that companies without the same data could never hope to match. Google is already a monopolistic powerhouse in tech, and the enormous amount of data that Google Analytics provides gives Google a competitive advantage that virtually ensures that it will never be dethroned. Winning a market in the short run can be harmless, but even a perfectly benevolent company achieving perpetual market dominance is concerning — and Google is far from a perfectly benevolent company.

Digital Inklings is a just a molecule of water in the vast ocean of the internet. If the internet were New York City, this site would be a messy newspaper stand in Queens that you stop at every so often for a candy bar and small talk with the owner, wondering afterwards how it survives amidst soaring rents. But small as it is, it’s my newspaper stand, dammit(!), and I wasn’t going to be a part of contributing to Google’s hegemony anymore. It was time to break up with Google Analytics. But this breakup revealed, as they always do, that things weren’t as black and white as they seemed, and there was plenty of blame to go around.5

Data hypocrisy and putting the genie back in the bottle

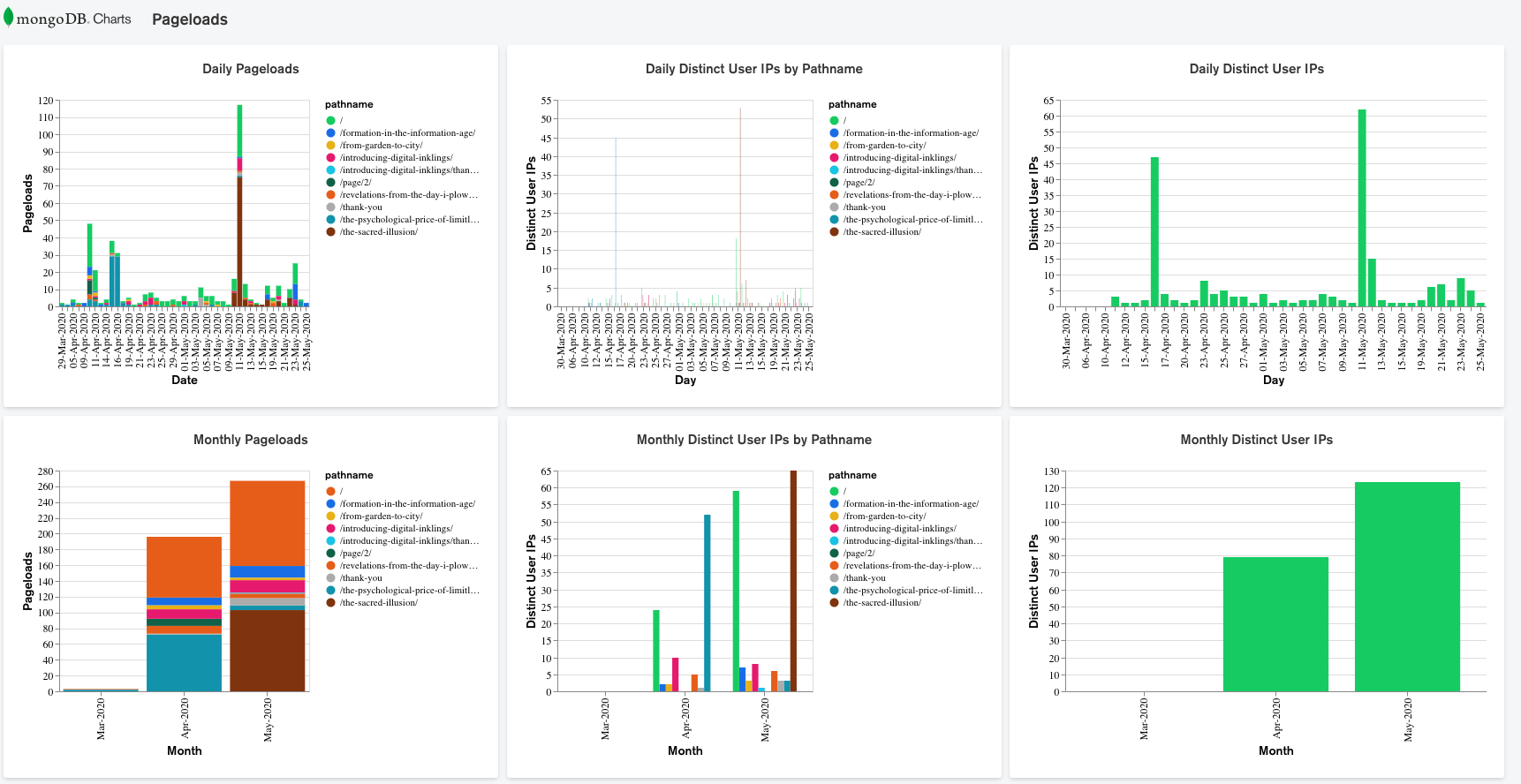

I’ll spare you the gory technical details of the analytics service that I built, but the end product, real time graphs of visitors to the site, are publicly visible here, and I’ve included a screenshot below.

If you compare my service with Google Analytics, you’ll notice one main thing — my service sucks. It only tracks one metric, pageloads, and can only split it up by what page you viewed and your IP address (which is my somewhat-error-prone proxy for unique users). Compare this with Google, which will tell you a user’s device, location, previous website visited, and much more. The graphs for my service are ugly, and unlike in Google’s dashboard, I can’t easily resize them to any period of time that I want or aggregate the results over a time period. I have no ability to know how many people are actively looking at the site at any given time, and I still have problems with date and time. There is literally no one on earth who would say that my service is “better” than Google Analytics.

Some of this is due to laziness6 — I’ll fix the chart scaling when I need to, for example, but right now it’s good enough for me. But much of this mediocrity is by design. I explicitly didn’t want to use a cookie out of respect for user privacy, and I didn’t want save user locations or what sites users came from. I wanted to record just enough data to know which articles people were reading and make sure I knew if the site was down. I imagined my stripped down service like a monk with a shaved head, a sort of ascetic form of analytics, with all the rejection of excess and moral superiority that comes along with it.

Once I finished the new service and deployed it, it was time to finally cut the cord with Google. But before I did, I wanted to run both services simultaneously for a week to compare my new analytics data with Google and make sure it was correct. But then one week turned into two, and then three, and I was still checking dashboards in Google Analytics. I was finally forced to admit my hypocrisy — despite my principles about privacy, having access the depth of data that Google gave me was fascinating, and I didn’t want to give it up. It was fun to know that someone in Europe read my blog last month. It was exciting to post a new article and see the number of people reading it in real time. It was helpful knowing where on the internet readers found articles in the first place.

My inability to cut the cord might just be a lack of philosophical backbone, but for high-traffic sites run by businesses, giving up analytics data is basically impossible. If every company competing in a market only had access to my limited pageload-only analytics data, it wouldn’t be a problem. But once deeper data is available to everyone, it would be competitive suicide to give up that valuable information for something silly like “user privacy”. Once the genie of personal data is out of the bottle, it’s hard to put him back in.

This also means that Google is almost definitely going to continue as the internet’s all-seeing eye for the foreseeable future. As a business, your priority is to get the data you need with the least amount of cost and hassle. Creating your own service, as I learned, either doesn’t give you the data you need, is a huge amount of work, or (mostly likely) both. Barring the emergence of a far superior competitor product (which would likely have the same business model of spying), you’re going to choose the standard plug-and-play option of Google, whose product will get stronger as it learns from 85% of the internet’s traffic. This genie is very hard to put back in the bottle.

Can we ever get to an internet free of the all-seeing eye — of Google or anyone else? Some have argued that we need the government to regulate online tracking and digital advertising. This is the route that Europe has taken through GDPR regulation, and I’m hopeful that we can learn from its successes and failures. But given that the US government has been a far worse actor than most companies in regard to digital privacy, I don’t entirely trust them to solve this problem. A better way is to give individuals the tools to control their data and online privacy. Many powerful technologies already exist — extensions that block trackers, VPNs to obscure location, end to end encryption in communication technologies, and cryptocurrencies for anonymous payments. But similar to companies, people also want to get the most out of the internet with the least amount of effort, and many of these tools are a lot like my analytics service — confusing, hard to use, and sometimes just jank. To see change, we need a wave of products that take these technologies and make them delightful to use, giving people the ability to use the internet both powerfully and privately.

And what about my own hypocrisy as I continue to run Google Analytics on Digital Inklings? I’ve wondered if it’s ok for an individual site like mine to collect some of the deep data that I find interesting and valuable as long as it’s not shared with a massive aggregator like Google. That fits more with our physical model of privacy, where a shop owner knows how long you were in his shop and what direction you came from, but doesn’t give that information to the city government to be aggregated into a map of every individual’s movements. And if removing Google Analytics from my tiny newspaper stand of a blog will have absolutely no effect on Google’s data dominance, does it even really matter? A principled stand is nice, but not having to fix my service when it inevitably crashes saves me a headache, which is also nice. There’s not a clear moral here, just like all breakups. But hopefully, we both learned something as a result of this relationship — Google learned that you read this article, and I learned that principled asceticism, in web development as in life, is not very fun.

Big thanks to Harrison Steedman, Baker Moran and my wonderful mom for reading drafts of this article.

Update (August 2, 2020)

When I published this article, this site still had a reCAPTCHA to keep spam out of my email newsletter form. Some readers pointed out that reCAPTCHA is owned by Google and used for the same sort of data collection as Google Analytics, so it was hypocritical of me to criticize Google Analytics while having a reCAPTCHA on my site. Despite the fact that the main takeaway of this article is that I am a hypocrite when it comes to surveillance capitalism, it was a fair point. I’ve replaced the reCAPTCHA with a simple question you have to answer correctly to be added to the newsletter, which should hopefully fool the bots and not present too much of a challenge for my lovely readers (and just in case, the answer is “dog”). Whenever the spammers start using

GPT-3, I suppose I’ll have to come up with a more sophisticated solution.

1. This is pretty meta considering that you’re reading this article right now, giving me a tiny dopamine hit. My sincere thanks.

2. This is why clearing your cookies, the internet browser equivalent of turning it off and turning it back on again, logs you out of all your sites.

3. I’m imagining a muscular bouncer, but given that this is supposed to be analogous to a snippet of code, it’s probably better to imagine this as the nerdy guy you went to high school with or a really intelligent corgi.

4. If this is genuinely your position, please read the linked article and reach out to me. I would be curious to hear arguments from a different perspective about this.

5. I’m mixing my metaphors here, a cardinal sin of writing, but as I already said, this is my newspaper stand, dammit!

6. I use laziness in a pithy way — making these charts beautiful is not anywhere as high a priority as most of the rest of my life, so it might be ugly by choice for a long time.